Have you ever visited a museum and wondered about the journey behind the exhibit? What inspirations and challenges shape the displays? To be honest, I had never given it much thought until I embarked on one of my own. It began as a student project, an exhibition for the university open day that introduced me to the fun and excitement of curation. Little did I know that this experience would ignite a passion and lead me to the school of Museum Studies, and ultimately, to Worcester medical museums, where I was entrusted with developing a display in the actual museums.

While these displays are obviously small and take no more than five minutes of visitor’s time, it is quite a complex journey requiring much time and effort. In this post, I will reveal the process behind the displays, sharing insights into how I crafted the final results you see in the museums.

(Disclaimer: While my approach might not be the best practice, it’s a reflection of my experience and how I tackled the task.)

Let’s begin with the “ART & ANATOMY” display at George Marshall Medical Museum. This exhibit resides in a desk case for temporary displays, typically refreshed every few months. I was given a task developing a display there, no specific topics, no particular objects. It was entirely up to me, whatever I wanted to do. It sounds liberating but actually it was very challenging, especially for someone relatively new to medical history like me.

The journey started with extensive research of everything that could be helpful to my tasks. I explored previous displays, went through medical history in general, including what students do for their GCSE, looked over antique and modern medical practice and immersed myself in the history of Worcester city. As a result of this exploration, the theme of ‘anatomy’ caught my interest. It represents a big leap in understanding the human body, advancing medical practice and is now considered as fundamental for every aspect concerning the human body. So I decided to centre my display around the theme of anatomy.

Start off with research and a note of the topics may be useful.

With the theme in place, I went through the museum’s collection, not physically but through the management system, in search of objects related to anatomy. The advantage of working in a smaller museum is that it takes not so long to look through the collection. It was during this process that I came across Alan Mann’s anatomical drawings and the compelling stories that would be great to be shared with a wider audience. I also spent a lot of time in our rare book store, where the old and rare publications are kept. As I went over most of the anatomy books in the collection, I noticed the diverse compositions - some with only text, while others featured simple or complex and detailed drawings, and some contained retouched or realistic photographs. This pointed up the importance of selecting the most suitable type of illustration which is crucial to the author. So basically, illustration, or art, played a vital role in the study of anatomy.

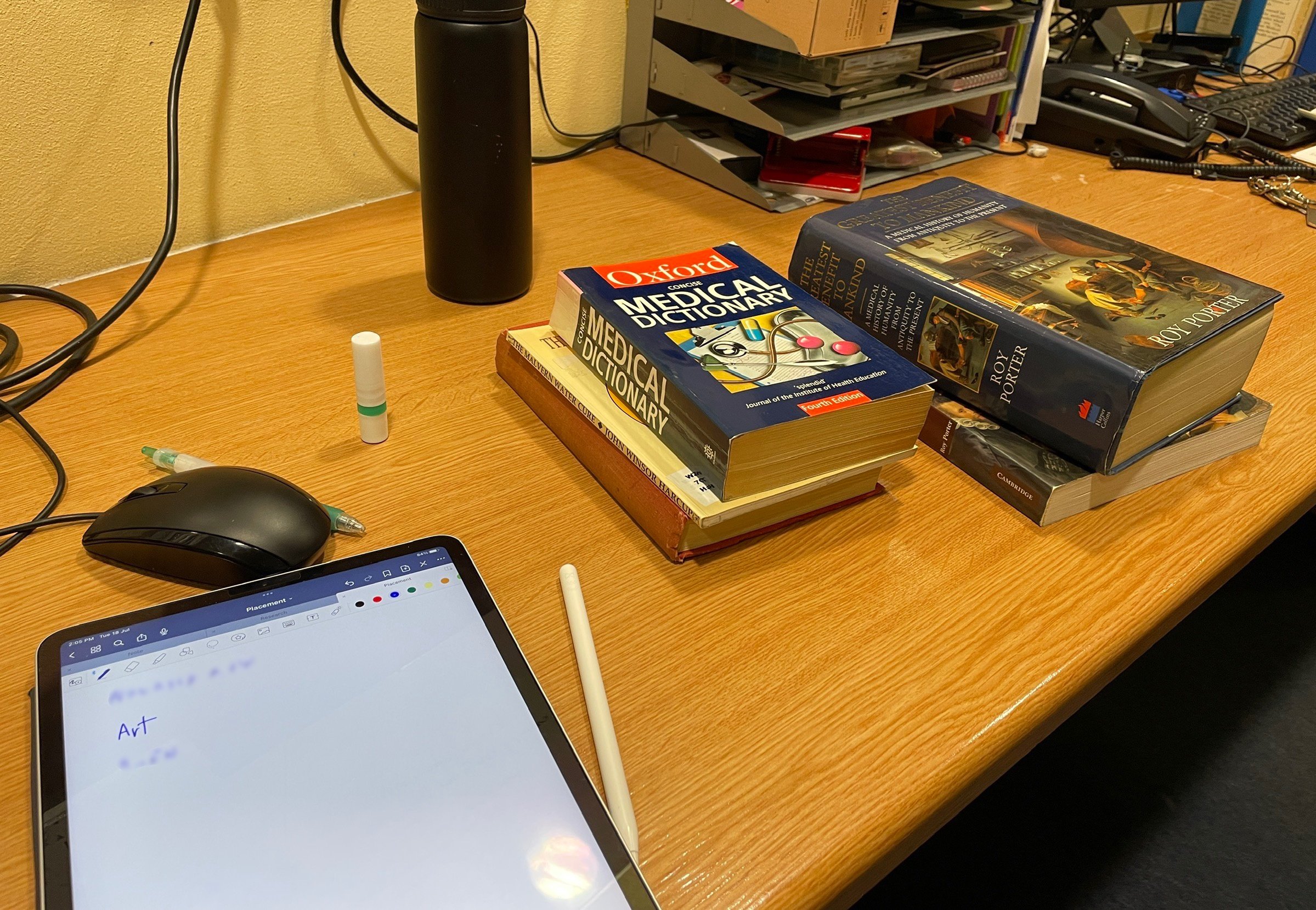

Getting myself comfortable sitting in the museum’s rare book store, going through anatomy books in the collection.

This discovery prompted a secondary research, focusing on the relationship between art and anatomy. A thread can be traced back to the Renaissance period when anatomy served creating masterpieces of art, and continues to the present day where art is an implement in understanding anatomy.

As the main concept was settled, it was the time to select objects that would convey the messages I am trying to present. Several items were chosen, each with a unique role, from a textbook of anatomy without illustrations, highlighting the significance of visual aids, to the famous Gray’s Anatomy, well known for its exceptional illustrations but the illustrator were outshined, to the story of a local pharmacist and his unique collection in our museum, and an atlas of the human body with layers that can be lifted and explored to demonstrate the body.

At the same time, the limited space in the case is taken into account. The display case was smaller than expected which meant I had to be selective about the number of objects on display. I carefully measured the case and tried with various layouts to make the most effective use of the space.

Trying out different layouts to find the best fit.

When the objects were chosen and the layout was fixed, it was now the time to carry out the plan. Objects were carefully removed from their places and delicately positioned within the case. The primary concern at this stage was to ensure that the objects were arranged in a way that minimises the risk of damage. It is a delicate balance, as museums aim to make their collections accessible to the public while also reserving them for future generations. Fortunately, all the objects in my display are in excellent condition, and the setup was completed without incident.

Last but certainly not least, I turned my attention to creating interpretation labels. These labels will guide visitors to the main themes of the display, providing descriptions of the object, and sharing the stories and narratives associated with the objects on display. Also the hope is that these labels leave visitors with some thoughtful ideas after their visit.

And there you have it - the entire process from the beginning to the final result of my exhibit. Though it may be a small display, a significant amount of time and effort has been invested in this work. So, if you have the opportunity, I encourage you to visit George Marshall Medical Museum and explore my display. Discover the tangled connection between art and anatomy and uncover the captivating stories behind anatomical art.

I cannot be sure how long the display will remain, but it won’t be forever. So please come and experience it for yourself.

A blog by Kanruthai Chongraks (Nahm)