OUTSIDE THE ASYLUM

Can you help George Marshall Medical Museum with a spot of family history research to find out about some people who were admitted to the Worcester City and County Lunatic Asylum in the 19th century?

Our aim is to share more patients’ stories, and to find out about their lives before admission and (where possible) after discharge.

susan quinton

find out more about susan quinton

Susan Quinton was admitted to Powick Hospital at the age of 62 in 1881. Susan was diagnosed with melancholia.

Susan Quinton was born as Susan Bevan (sometimes spelt Bivon) in 1826 and baptised on the 17th of May. Her father John Bevan was a labourer and lived with his wife Sarah Bevan in Blakebrook, Kidderminster. By the time she was 15 years old, Susan had already moved out of her parents’ house. Susan lived with forty-year-old couple Bejamin and Sarah Richards, their three daughters and their three sons. Susan Bivon, Sarah Bivon, and Maria Beasley, all aged 15, lived with the Richards family. They lived on High Street, Stourbridge and it is undisclosed what the relationship of the three girls was to the Richards family, but it is possible they were hired as servants. Susan Bevan’s parents, Sarah and John, lived alone in Sutton Common, Kidderminster.

In 1850, Susan Bivon married William Quinton, fifteen years her senior, in Kidderminster. Susan’s father was recorded as John Bivon, a labourer. William and his father George both worked as weavers. Susan also worked as a weaver, and they may have met through this shared profession. William Quinton had an interesting past before his marriage to Susan. In 1832 William Quinton married Mary Ann Carr in Ribbersford, Worcestershire. The pair had at least four children as seen in the 1841 census. John Quinton was born in 1833, Thomas in 1836, Julia in 1838, and Edward in 1840. This meant William’s marriage to Susan was in actual fact his second marriage, and it was bigamous. Bigamy is the crime of getting married whilst still being married to someone else. William was found out for this in 1864, he was put on trial on December the 12th and imprisoned for one month in Worcestershire.

In 1851 after one year of marriage, William and Susan Quinton were still working as carpet weavers and living in Kidderminster. Susan became a stepmother, as she lived with William’s son John, now 17, Thomas, 16, Julia, 12 and Edward, 10. Interestingly the couple also lived with children Charles Quinton, 8 and Martha Quinton, 5. Baptism records do not show if Martha and Charles were Susan’s or Mary’s children. Both children were born before Susan and Williams marriage, so it is presumed their birth mother was Mary.

The oldest children moved out of home, and by 1861 Susan and William had moved back to Wilton in Wiltshire, where William was born. The couple still worked as carpet weavers, as did William’s son Charles Quinton who still lived with the couple at age 18. The youngest child, Martha Quinton had also moved back to Wiltshire but lived in an area called Sailsbury, St Thomas. Martha was employed as a servant to Samuel and Murray Burch, who were presumably reasonably wealthy, living at 132 Catherine Street.

Susan and William Quinton eventually moved back to St Mary in Kidderminster as a couple. They had two young boarders living with them in 1871, William Smith who was age 15 and Samuel Hepwood, a blacksmith, who was age 17. Ten years later, their living situation had changed drastically. Susan became the head of the household in 1881 and was recorded as a winder in a carpet works. Susan lived with three female lodgers who also worked in the carpet works, Sarah, 30, Mary 18, and Annie, 15. Susan’s husband William Quinton was an inmate at Kidderminster Union Workhouse in 1881. Inmates of this particular institution ranged from just 6 months old to 90. The master of the workhouse was Thomas Hope, who lived there with his wife and seven-year-old daughter. In this year, there was about 338 inmates. Workhouses were built to accommodate the poorest of society who had no where else to go, and where possible, people were put to hard and inhumane labour. Only the elderly, sick, and very young were excused, William Quinton was 71 at this time.

That same year, Susan was admitted to Powick Hospital. Susan Quinton was admitted on October 7th, 1881, with melancholia. As seen, it had been a difficult time for Susan being separated from her husband and having boarders living in the home she once shared with William. The cause of her condition was instead put down to ‘poverty’ and her case notes state she had been living with a relative. We also find out that William had been in the workhouse three years by 1881. Susan’s case notes state she had only been ill one week but had “suicidal tendencies” and “delusions… that she was constantly pursued by the police and other persons who intend to tear her to pieces and hang her.”

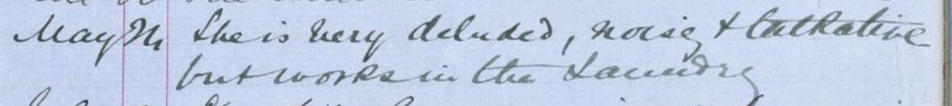

Susan was described as having “thin iron-grey hair” that was “matted and dirty, and her body covered with the marks of flea bites.” After one week at the institution, these physical ailments had improved, and she was generally “much brighter.” Susan spent a lot of her time in the laundry at Powick and her good work was constantly mentioned throughout her case notes.

However, in general, her condition appears to have worsened over her stay at Powick. One year in, Susans case notes state that she believed people were talking about her “saying she is a whore and a murderer.” She also developed other physical ailments such as a “ringworm wound in the nape of her neck” in 1883. After just over three years at Powick, staff found she became “violent and a very little thing caused her to break out into a fit of noisy abuse.” Staff also believed her delusions worsened, in 1895 they stated Susan believed “people were robbing her of her money.” In 1902 her notes claimed she thought “her relatives were being murdered” at Powick, which later developed into the belief “her children are here and being murdered and cut to pieces.” Susan also struggled with her weight at times and her case notes often commented on a ‘loss of flesh.’

The Letter

In 1894, after thirteen years at Powick Hospital, Susan Quinton wrote a letter. Susan addressed it to a “Mr William Bevan, 88 Sutton Road Kidderminster,” who was her brother. William Bevan was born on the 27th of February 1825 in Norton Canon, Hereford, making him one year older than Susan. William Bevan married his wife Eliza Griffiths on the 30th of September 1844 in St Mary, Kidderminster. Eliza also came from humble beginnings working as a servant. William worked as a gardener and the couple had six children, three girls and three boys. Their first, William, was born in 1848 and their last, Joseph, was born in 1860. The family continued to live in Kidderminster and settled in Sutton Road at some point after 1871.

By 1881, the year Susan was admitted to Powick, William Bevan and his wife Eliza still lived with their youngest son Joseph George Bevan, who had become a police constable at the age of twenty-one. The Bevan’s also lived their grandsons Caleb Bevan, aged eleven, and William Frederick Meek, age four. From research, it appears that William and Eliza’s daughter Matilda, born in 1853, had her son Caleb on the 6th of September 1869, when she was just 16. It is only Matilda recorded on the birth record. She had her second son with her husband David Meek on the 9thof July 1876. However, by 1881 Matilda had moved to London and was living with her new husband George Cardinal whilst Caleb and William lived in Kidderminster with their grandparents.

It was to this household that Susan addressed her letter on June 2nd, 1894. She addressed the message to both her brother and sister, although a biological sister for Susan could not be found in the records. Susan writes in an extremely scared manner beginning “I am in danger of my life the doctor wants me to go to Australia or else be cut to death or hung.”

Susan said she was “worse than ever” in the letter and claimed that somebody had “threatened to strike me naked and cut me to pieces.” This letter gives insight into Susan’s state of mind and feelings towards her hospital admission. Susan was evidently fearful for her life at this point and distressed by her situation. Susan also expresses her frustration at people not giving her her “child’s money,” which matches the case notes we have available written by staff.

Susan’s Case Notes: “fancies people are robbing her of her money”

Susan’s letter: “I don’t think it is just and right for me to be kept here and for him to have my child’s money

Susan pled with her brother and his family for help out of the institution. She stated that “Monday is Committee day I should like of you to come.” Susan went on to say, “please give my best love to joe and his wife and tell him to come quick as possible.” Susan’s nephew Joseph was a police constable at this time and was living with his wife Sarah Elizabeth Bevan in Kidderminster. We do not know if her family ever received this letter or responded to her pleas, but we do know that any attempts they may have made to help discharge her, were unsuccessful. Susan ended her letter with this, “P.S. please come as quick as possible or perhaps I might be gone.” Susan expressed clear desperation for help out of the institution. From her case notes and the England Census, we know Susan in fact stayed at the institution for another twenty-three years.

Susan passed away at the institution on the 2nd of July 1917 after a total stay of 36 years at Powick Hospital – her cause of death is unknown. Susan’s husband William Quinton passed away on June the 5th 1890 at the “poor house,” age 79. This was nine years into her long stay at the institution, and we cannot know whether Susan was told of her husband’s death.

Research by Alice Fairclough, 2025.

To view Susan’s patient records, click here.

Go back to find out about more people who were patients at the asylum.