A placement week may be seen by some as a chance to get more experience in the field you want to work in, or for others may be seen as something you have to do. But, I can assure you, after my week at The Infirmary, a placement week means much more. During my placement week, as part of being a Univeristy of Exeter History student, I was given the exciting task to explore other museums/educational sites in Worcester. Through visiting other museums and tours in Worcester, I have experienced the interconnectivity of the history shared, and learnt vast amounts of history about my home city. One of the most significant figures who was shared across the museums was Charles Hastings, founder of the Provincial Medical and Surgical Association, which later became known as the British Medical Association (BMA). The guided city tour with Worcester Walks beginning at Guild Hall, made links with Charles Hastings as did the Tudor House and Museum and Worcester City Art Gallery and Museum. Therefore, I became quickly educated on the history of The Infirmary and BMA through visiting other places, whilst having an amazing time!

Firstly, I began with the guided city tour with Worcester Walks, which began outside Guild Hall and progressed to the river side, the back of the Cathedral and then ended on Angel Street. Our guide was a woman named Miriam, who was actually a nurse during the time the Charles Hastings Building was in fact the Worcester Royal Infirmary. As you can imagine, I was very enthusiastic about hearing her words on the Infirmary and what life used to be like, especially being a nurse herself! The tour was very informative and took us on a beautiful walk around the city. Although, I would recommend you feel awake and prepared to take it all in as it is a lot of information, and also a long walk (especially when it rains). When we arrived outside of the Cathedral, Miriam pointed us towards one of the stained glass windows and recalled the story of Charles Hastings. Immediately I made the link between the Infirmary and the Cathedral, as Miriam highlighted the significance of Charles Hastings with his contribution to medicine and formation of what we know as the British Medical Association today!

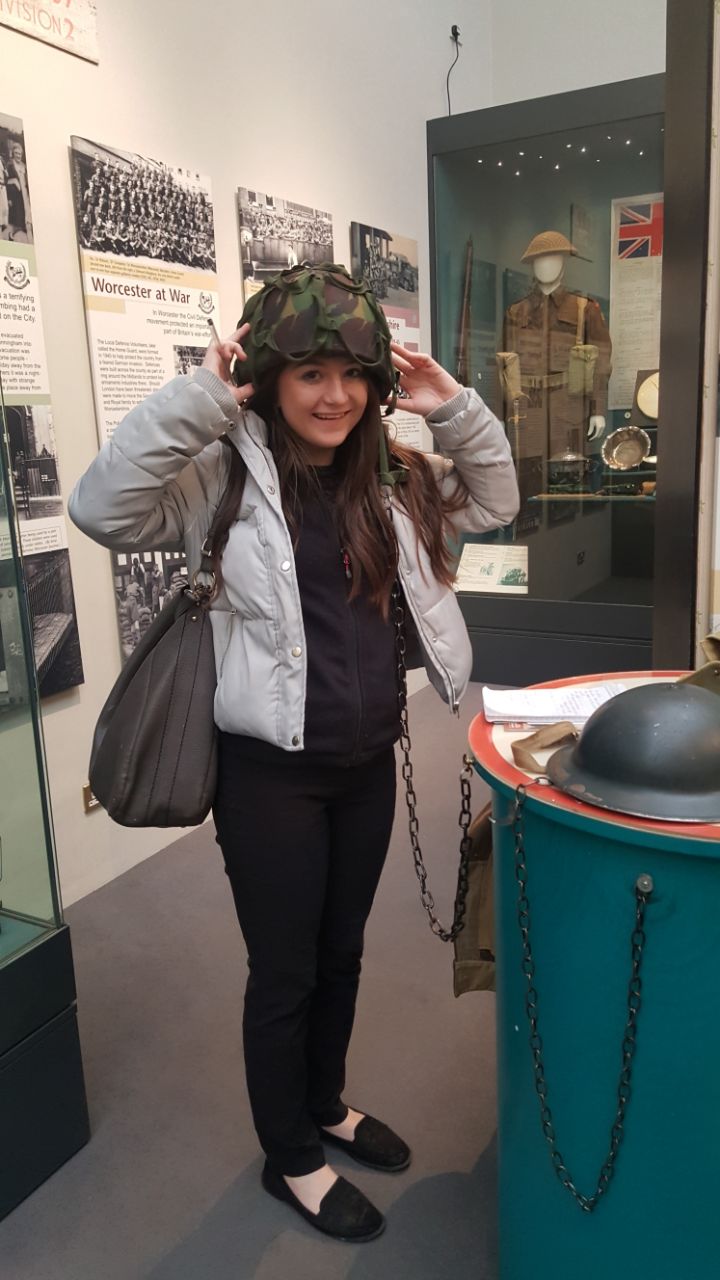

Following on, I then visited the Worcester City Art Gallery and Museum, just past Foregate Street. I was greeted by a lady in a reconstructed Chemist exhibit, known as ‘Steward’s Chemist Shop’. This showed a fantastic collection of different pharmaceuticals used from 1876 till the shop closed in 1973. Medicine again! This was definitely the most authentic and interactive elements to the museum that I enjoyed. Whilst walking round, I spotted a familiar face in a portrait painting held on a wall, Charles Hastings. Another link to the Infirmary! Wandering round the exhibition you feel like you are literally travelling through time with all of the different soldier’s costumes.

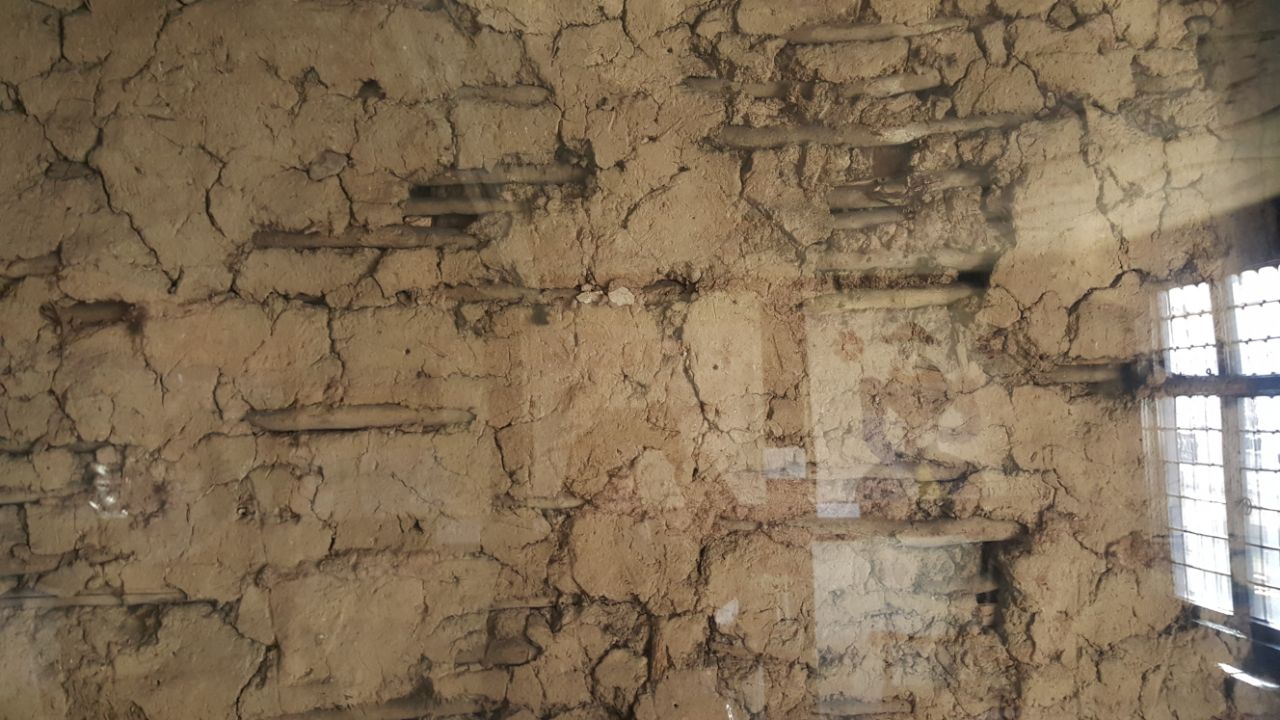

The following day I visited Tudor House museum, a building consisting of three houses all dating back to the 16th century. Here, we were given a tour of the museum with great detail into each object. Each room is set up as a different style, either a bathroom, kitchen, dentists/doctors, with amazing objects to suit. The display of how the wall was made is fascinating and gives the audience a real insight into the foundations of the building. In the section for the famous people of Worcester was Charles Hastings, complete with his life story, which was great to see. Overall, I think the Tudor House museum is a great way to explore history as the set up helps you experience the reality of how it was when it was used. Similar to the Infirmary, Tudor House relies on volunteers to help keep it running which demonstrates the amazing work these volunteers are doing with the quality of the museum!

The Commandery was one of my final visits during my placement, and what a magnificent end! The Commandry is a grade I listed building, with over 800 years of history and most famous for being the Royalist Headquarters during the Battle of Worcester 1651 in the Civil War. The Commandery was the only place where I couldn’t find a link to Charles Hastings. However, the Commandery offered spectacular views of the garden (especially when the sun is shining) and a great insight into the Civil War and Battle of Worcester. There were hats to try on, swords on show and some amazing architecture which really promoted the museum. I would argue that the Commandery was more suited to older audiences, rather than younger, because of the style and layout.

The Infirmary was my favourite museum I visited in terms of interactivity and engagement, some potential bias there, as it is filled with amazing touch screens to listen to oral histories, and models of bodies etc. The constant music of Elgar playing in the background really links to Worcester’s history, creating a positive environment to the museum. A medical atmosphere is accomplished with the sound of a surgical beep in the background, transforming the guests experience. Once again, the audience are really catered for from old to young, with more recent history for those who would remember, and interactive models and games for children to get involved in. Considering the space given is significantly small, the museum has accomplished in educating and accommodating for its audiences. And of course, Charles Hastings! The building itself is named ‘The Charles Hastings Building’ and there are vast amounts of information on him too!

Holly Ashley

University of Exeter, Placement Student